'Black Narcissus,' 'The Wild Robot,' and Christian Missions

"I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some."

How are a 1947 British psychological drama and a 2024 DreamWorks Animation film similar, and what do they have to say about Christian mission work? You might be surprised.

Black Narcissus (1947)

There are some films that simply defy the day and age in which they were made. Films so remarkably crafted, technologically advanced, and thematically rich that they don’t just surpass their peers, they belong in a different class entirely. 2001: A Space Odyssey comes to mind, as does Jurassic Park.

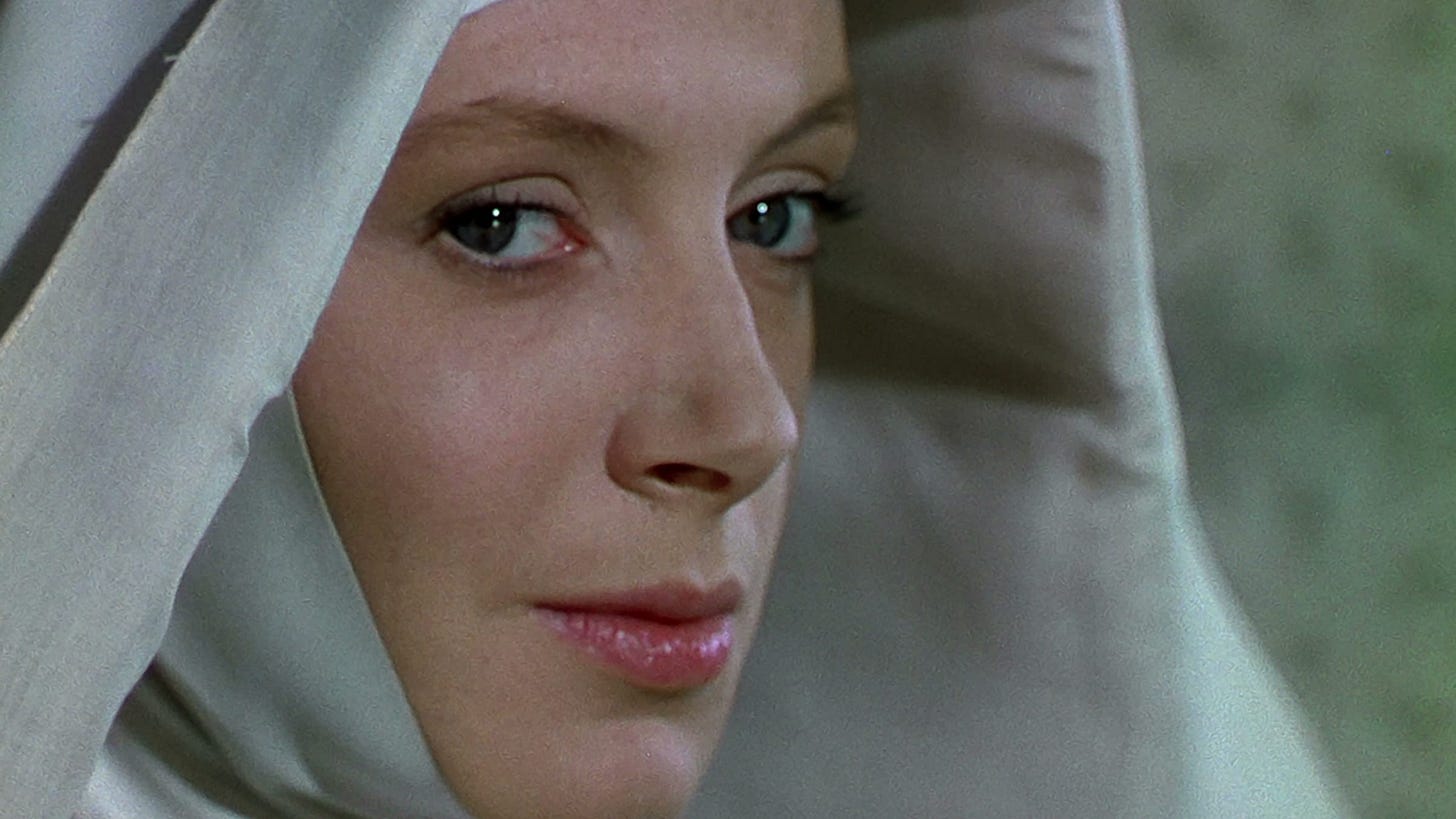

Most recently, I felt this phenomenon when watching Black Narcissus. “Set during the final years of British colonial rule in India, the film depicts the growing tensions within a small convent of Anglican sisters who are trying to establish a school and hospital in the old harem of an Indian Raja at the top of an isolated mountain in the Himalayas. The nuns have trouble adapting to the harsh climate and antagonistic population. They come to rely on the help and advice of the Raja's British agent, a cynical Englishman whose attractiveness and panache become a source of temptation for the sisters.”

Black Narcissus is a technical and visual marvel years ahead of its time. The vibrant colors, the stunning visual effects, the shot selections, the camera movements…I truly can’t wrap my head around this being made in 1947. The film’s close ups are often so extreme you feel uncomfortably close to the characters, and the varying shots of the cliffside setting are equal parts dizzying and stunning.

I cannot speak highly enough of the craftsmanship on display, but beyond its cinematic beauty, Black Narcissus is a rich examination of temptation, seclusion, and evangelism within religious orders. In running from all prior doubts and temptations via their vows, the nuns in the film find themselves ill-equipped to fight temptation when it inevitably arises at their new post.

One of the nuns, Philippa, identifies this very challenge, saying, “I think there are only two ways of living in this place. Either ignore it or give yourself up to it. Neither would do for us.”

In ignoring the specific needs of their placement in the Himalayas, the nuns can’t properly minister to the people. But if they fully “give themselves up to” the ways of the world around them, they would be ignoring their Christian calling altogether.

This dilemma showcases front and center the pitfall of their missionary work, and it's a problem historically associated with missionary work as a whole: a tendency towards colonialism.

To be fair, I think the concept of Christian missions is often treated unfairly by nonbelievers who either don’t fully understand mission work or deliberately misconstrue its purpose.

That said, missionary work that isn’t fully Christ-centered is not only bound to fail, but can barely even be categorized as missions.

Black Narcissus comments on this very issue, showcasing the ways in which the nuns’ time in the Himalayas often resembles said colonialism rather than selfless service, gospel sharing, and relationship building. This was undoubtedly the intent, with the film releasing only a few months before India achieved independence from Britain in August 1947. From the film’s perspective (and from a historical context), Britain’s Christian mission work at the time was largely inextricable from its colonialism.

Despite the nuns’ religious devotion, they allowed no room for God’s grace with people at “the ends of the earth.” Instead, they other the Indian community (“They all look alike to me,” one nun crudely remarks) and expect that community to learn their English language, customs, and, seemingly only by extent, their religion.

Put simply, these characters make no effort to understand the culture in which they establish their mission, instead expecting the local population to adapt to their ways. And while Paul in the Bible instructs Christians to not conform to the patterns of the world, he also made it clear that to truly minister and evangelize to people, we must understand and (to an extent) live like those people.

“To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some.” - 1 Corinthians 9:20-22

It’s no surprise these British nuns abandon the Himalayan mission at the story’s conclusion. Film critic Dave Kehr describes the film’s ending as a “retreat from something that England never owned nor understood.” And without that understanding, there was no real hope of spiritual transformation.

The Wild Robot (2024)

I had the pleasure of writing recently about The Wild Robot for Arts & Faith after it was voted 10th on the 2024 Ecumenical Jury. Reflecting on the film, particularly in such close proximity to my viewing of Black Narcissus, allowed me to see the stark contrast in its view of Christian service and mission work.

Nominated for three Oscars, The Wild Robot stars Roz, a housekeeping robot marooned on an island with only forest animals to serve. She realizes that if she is to help these animals, she needs to understand them, looking not to her own interests or programming, but to the interests of her neighbors.

The result is a character that exemplifies the life of service every Christian should strive for. Roz cares for the orphan (raising and nurturing a gosling), loves her enemies (such as the fox who stole from her), lives at peace with everyone (helping every animal survive a ruthless winter), and even is willing to lay down her life for her forest friends.

Roz’s selfless tactics seem strange to say the least. The animals often ridicule her counterintuitive way of living, which goes against every natural instinct or “circle of life” mantra they were born to. But eventually they realize that this unwavering form of love and kindness isn’t just a lifestyle choice...it’s the only way to truly live.

Roz has become a new person (literally, the compassion she now feels has rewritten her original code), and in the process, has transformed the hearts and minds of an entire ecosystem. By the film’s end, the animals continue to spread Roz’s story and message in a way that, dare I say it, reminds me a little of Christ:

“A robot fell right out of the sky. Roz. She had some strange ideas. Thought kindness was a survival skill. And you know what? She was right.”

The Christian Mission

Through these two very different films, viewers are painted a picture of what faithful Christian service and evangelism looks like: Christ-centered ( “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind”) and community-oriented (“Love your neighbor as yourself”).

The Christian mission is not about making “othered” people more like us; it’s about showing others the love God has shown us, and sharing the good news of His salvation with them.

It’s not about avoiding the outside world altogether for fear of sin; it’s about understanding and living in the world (though set apart) so that we can better serve and minister to its inhabitants.

Black Narcissus paints a tragic and devastating portrait of what an isolated, apathetic faith can become. The Wild Robot points to the transformative power that simple acts of love and kindness can have on the world, if one merely pays attention to its needs.

So the next time you’re looking for a thought-provoking double feature on movie night, consider this unusual pairing. You’re in for quite a commentary on the Christian life.

“Make your light shine, so others will see the good you do and will praise your Father in heaven.” - Matthew 5:16 CEVDCI