Disney Live Action Remakes and the Ship of Theseus

How much reinterpretation can a story withstand before it stops being the story we loved?

The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment introduced by Plutarch in the first century. Though if you’re like me, this philosophical question wasn’t introduced to you until 2021’s WandaVision. As Vision succinctly puts it in the show, “The Ship of Theseus is an artifact in a museum. Over time, its planks of wood rot and are replaced with new planks. When no original plank remains, is it still the ship of Theseus? If those removed planks are restored and reassembled free of the rot, is that the Ship of Theseus?”

Put another way, how much can be changed about an object before it becomes a different object entirely?

This ancient dilemma has been on my mind a lot lately, because the modern cinema landscape has provided audiences with a fascinating new experiment evocative of the Ship of Theseus: Disney’s live action remakes.

Remakes are far from a new concept for Hollywood. From the earliest days of film, studios would remake the same films, oftentimes even from the same director. Alfred Hitchcock twice directed The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, 1956). Cecil B. DeMille directed two iterations of The Ten Commandments (1923, 1956). Michael Haneke directed the original Funny Games (1997) and its American remake (2007), as did George Sluizer with The Vanishing (1988, 1993). A Star Is Born has now been made four times (1937, 1954, 1976, 2018), the most recent of which garnered eight Academy Award nominations.

This certainly isn’t a film-exclusive phenomenon either. Taylor Swift famously released “Taylor’s Version” re-recordings of her first four albums from 2021 to 2023. Theatrical productions are periodically restaged, and literature sees constant revisions, expansions, and new language interpretations of the same publications.

So what is it about Disney’s live action remakes that feels so different? And, even worse, so futile?

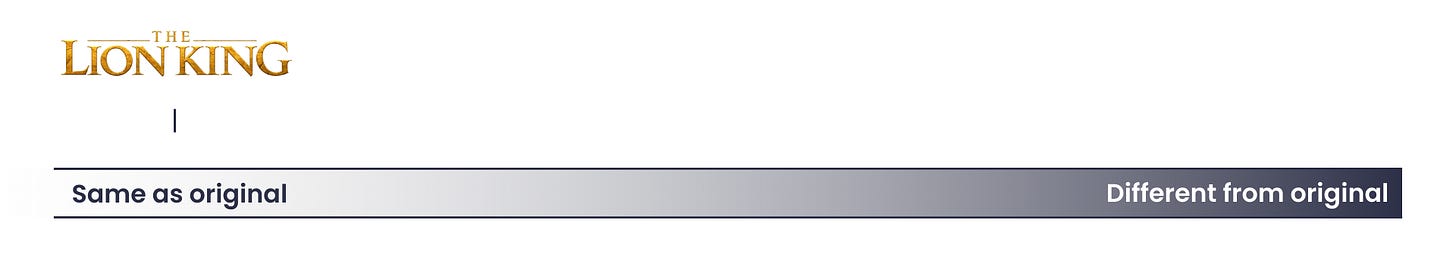

That’s where the Ship of Theseus comes in. Every film remake is its own Theseus experiment, needing to make enough changes to justify its existence without changing the core identity of the original. Let’s call this the Thesian Line: a remake’s balancing act between change and identity. And, as we’ve seen with Disney’s track record, problems arise no matter where they fall on that Thesian Line.

A Baseline

While I’m most interested in analyzing Disney’s 2025 live action remakes, it’s helpful to look at their historic releases to establish a baseline for where films lie on this Thesian Line.

On the far left (live action films most similar to their animated counterparts) we have 2019’s The Lion King. While the “new” draw of this film was its photorealistic depiction of the animal kingdom, nearly everything else is remarkably similar to the 1994 original, even down to the cast and crew. James Earl Jones was brought back to reprise his role as Mufasa. Composer Hans Zimmer returned to revisit his Oscar-winning score from the original. Even the film’s shot selections are uncannily replicated, such as Simba’s reaction to his father’s death.

On the far right (live action films completely different from their animated counterparts) would be 2016’s Pete’s Dragon, a film by David Lowery so unlike the 1977 original that the title and main character are largely where the similarities end. The original film is a quirky and fun musical in the style of much of Disney’s 60s and 70s output (The Happiest Millionaire, Bedknobs and Broomsticks), with a boy and his dragon’s antics in a small coastal town. The remake shares more in common with films like E.T. the Extraterrestrial than its own predecessor, an emotional and serious meditation on man’s relationship with nature featuring a completely different setting, cast of characters, and plot.

But, as always, the more interesting examples lie somewhere in the middle. Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella (2015) is a beautiful middle ground of the Thesian Line, retaining the core elements of the 1950 animated film while modernizing and expanding the story. The film still follows Cinderella and includes her cruel stepmother and stepsisters, the prince’s ball, the fairy godmother, the pumpkin carriage, the glass slippers, you name it. But Cinderella’s character is fleshed out. We see her father instill values in her that she carries throughout the film. We feel the hurt when she then loses her father and is subsequently mistreated by her step-family. Cinderella even meets the prince at multiple points in the film, establishing their romantic connection as more than just a single night’s fantasy.

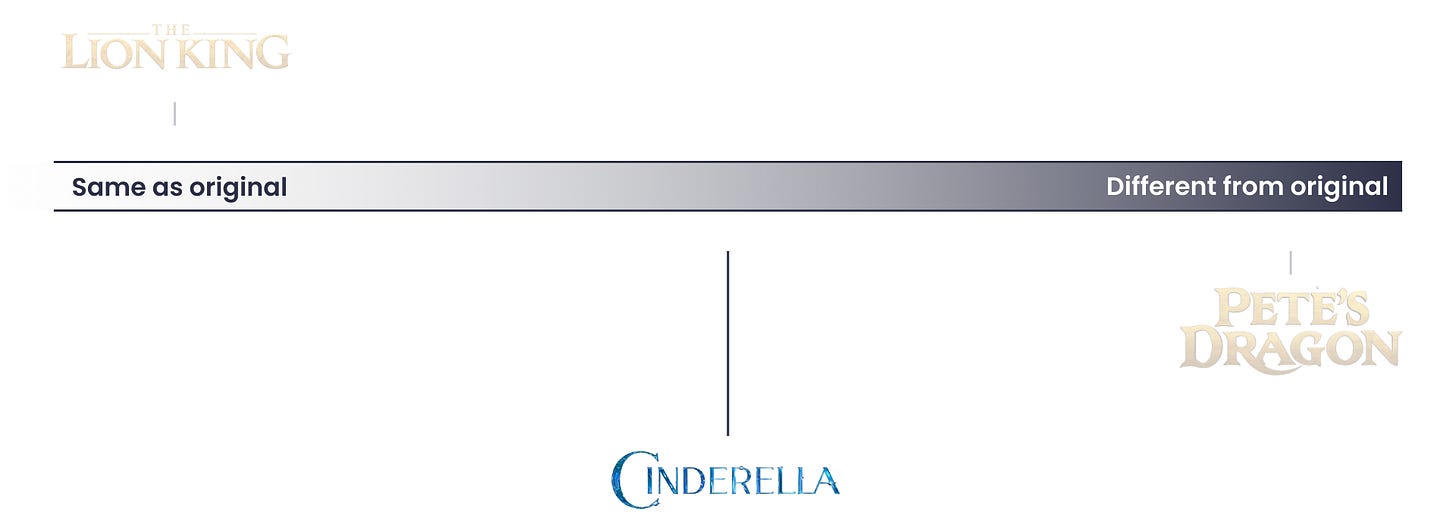

From there we can fill out the Thesian Line with Disney’s other remakes. The Jungle Book (2016), similar to Cinderella, maintains the essence of the original while updating and reimagining it for today’s audiences. Beauty and the Beast (2017), Aladdin (2019), Pinocchio (2022), and The Little Mermaid (2023) fall further left on the line, sticking closely to their animated counterparts with a few small revisions and expansions. Meanwhile, Alice in Wonderland (2010), Dumbo (2019), and Peter Pan and Wendy (2023) all differ greatly from the original films, to the point where one could almost argue they aren’t remakes at all (indeed, 2010’s Alice in Wonderland acts as a pseudo-sequel rather than a straight remake and isn’t listed in the chart).

Even when a film acts as a pseudo-sequel or a radical reimagining, its very existence as a new iteration of a familiar property forces a confrontation with the Ship of Theseus dilemma: how much can the narrative, characters, and themes evolve before the connection to the original becomes merely titular, challenging our understanding of what constitutes its core identity? While such films position themselves as "different from original," they still test the boundaries of the Thesian Line by asking whether a shared namesake alone is enough to tether a new creation to its predecessor.

A Trend Emerges

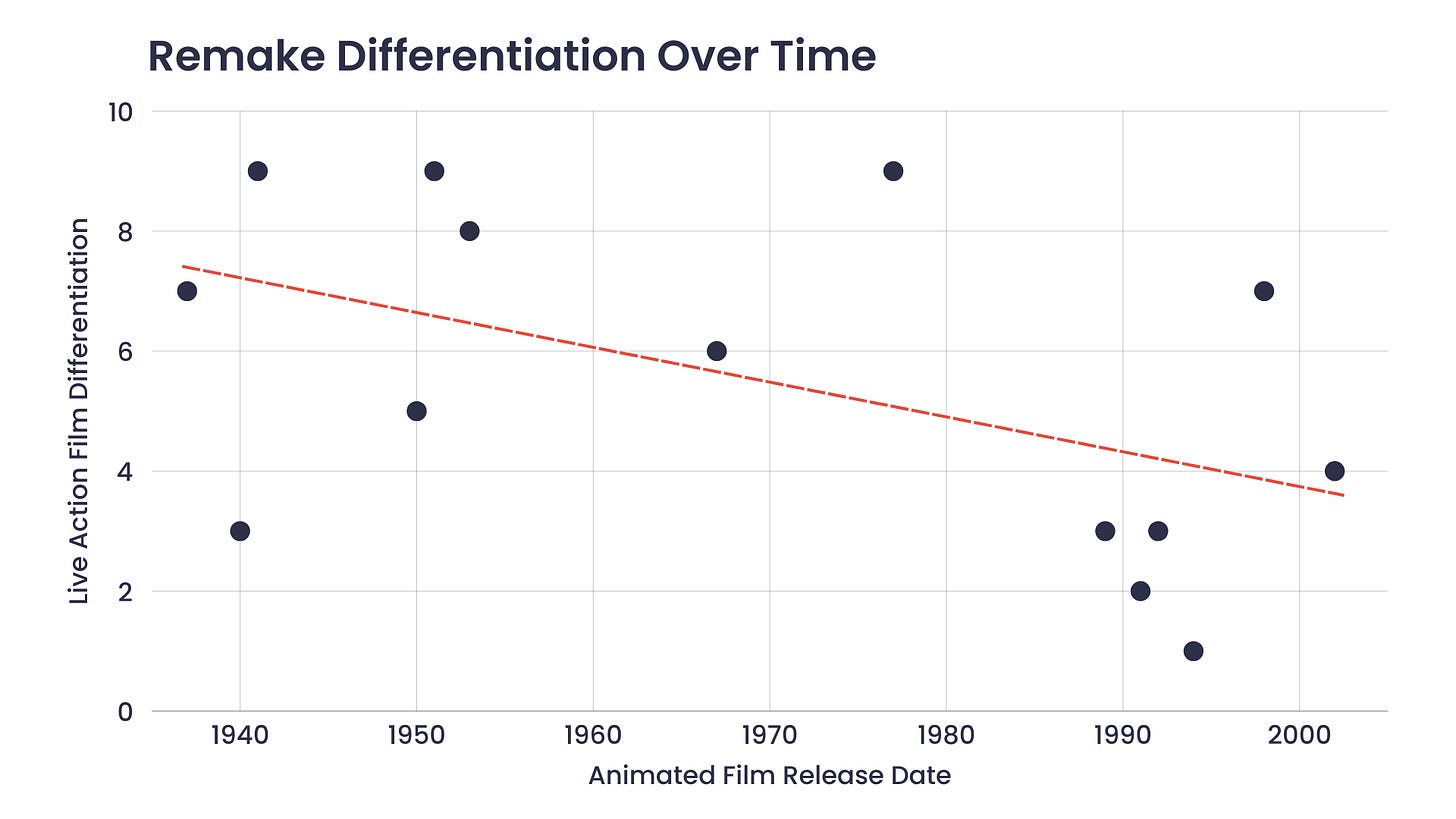

While I’ve only briefly touched on these films, we already start to see an interesting picture emerge for Disney’s Thesian Line, and with it, a few patterns. Namely, Disney appears to exhibit more creative freedom when remaking older films compared to newer ones.

Nearly 40 years passed between versions of Pete’s Dragon, 60 between Alice in Wonderland, 70 between Peter Pan, and 80 between Dumbo. These films frequently exhibit outdated societal portrayals and thus an obvious need for modernization, but beyond that, they demonstrate a difference in narrative styles. Early Disney animation features surprisingly episodic and slice of life storytelling that is rarely found in modern family films. Characters go from event to event with little-to-no connective tissue, and as a result, many of these remakes attempt to impose a more singular narrative around the film’s events.

By contrast, Disney’s most similar live action remakes have less than 30 years between iterations, such as only 25 years between versions of The Lion King (believe it or not, next year’s Moana remake will arrive a mere 10 years after the animated original). When it comes to these relatively recent original films, their narratives and characters still largely work in a modern context and can go unchanged for the remakes.

But perhaps most importantly, these remakes have to account for nostalgic audiences.

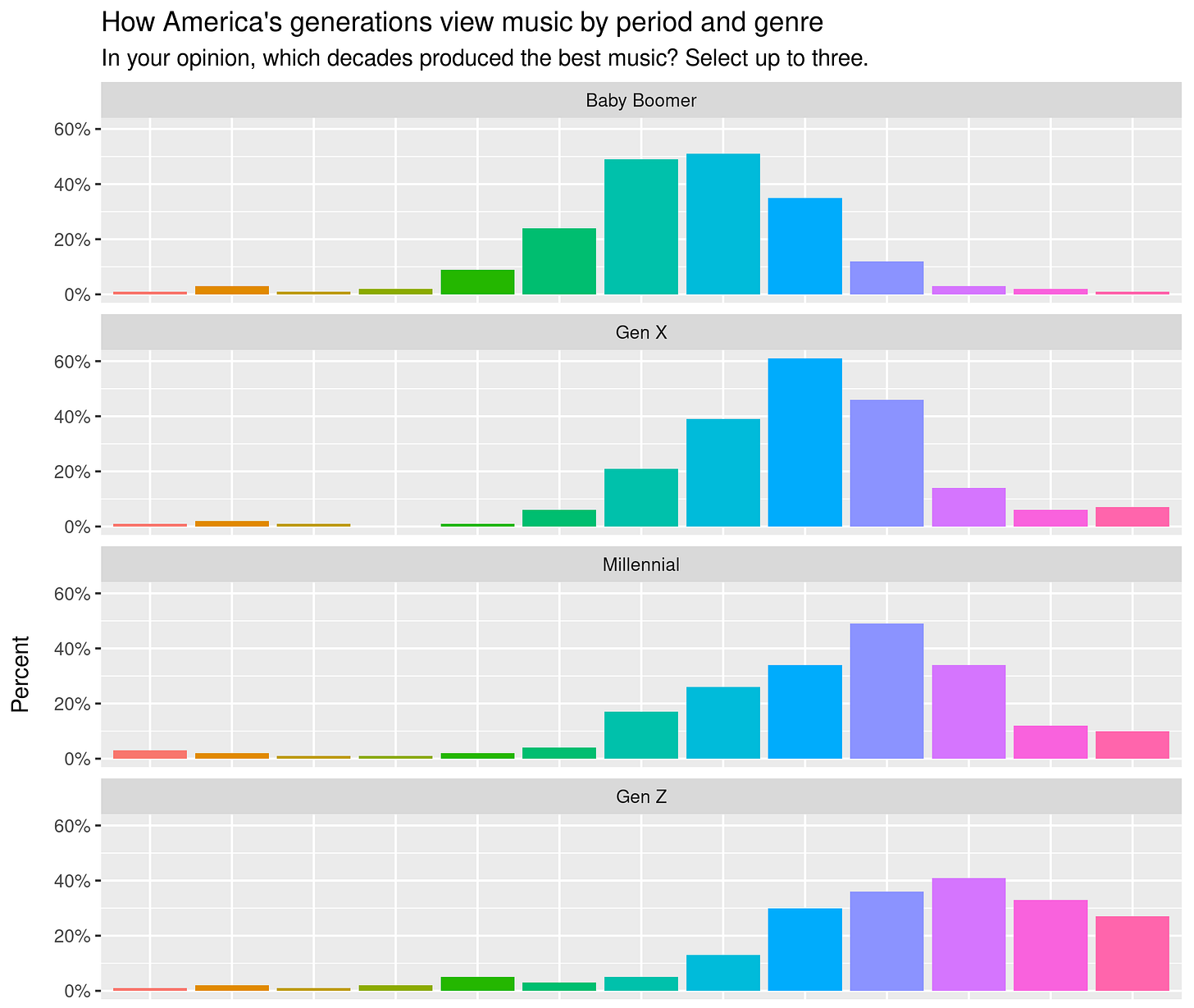

I’ve yet to mention nostalgia, an undoubtedly huge component for both the studio and for audiences when it comes to the appeal of these live action remakes. And while nostalgia comes into play for any remake (“wow, I love that old film and want to see it new”), nostalgia is strongest when an audience has early memories associated with the property. Just look at this survey of how American generations perceive music by time period. Unsurprisingly, each generation thinks the music of their youth produced the best music.

In the context of these remakes, when Disney is remaking 1941’s Dumbo, they can make as many changes as they want with very little concern for audience blowback (the 80+ year old theater-goers don’t seem to cause much of a raucous). But when remaking films of the Disney renaissance (1989-1999), the studio must account for the nostalgic expectations of Millennials who grew up with those films. Look no further than the (frankly racist) outrage when Disney announced that Ariel would be played by African-American singer and actress Halle Bailey in The Little Mermaid. If changing just the race of a beloved character resulted in backlash, why would Disney stray further than necessary from the original films? Change only seems to bring controversy.

Disney’s Live Action Remakes in 2025

And that brings us to Disney’s strange pair of 2025 remakes: Snow White and Lilo & Stitch. When applying past learnings from the Thesian Line, one would anticipate that Snow White would stray further from its 1937 original, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, while Lilo & Stitch should be a fairly faithful adaptation only 20 years after the animated version (2002).

And to an extent, that’s true. 2025’s Lilo & Stitch sticks fairly close to its expected formula, while Snow White oftentimes barely resembles its nearly 90-year old predecessor. But a deeper look at these films suggests their placement on the line is much more complex than my simple binary allows ... and furthers the debate of what makes up a film’s identity. At what point is an altered creation no longer the Ship of Theseus?

“The PC Snow White”

Disney’s new Snow White film was seemingly doomed before it even began. After being cast in the lead role, actress Rachel Zegler made waves in 2022 for her critique of the original film’s “extremely dated...ideas of women,” adding, "People are making these jokes about ours being the PC Snow White, where it's like, yeah, it is - because it needed that."

An honest evaluation of the 1937 film shows a lot of truth to her statements. I’ve written in the past about a Christian’s perspective on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and that analysis readily admits that Snow White’s character is underdeveloped and a poor representation of womanhood.

Nevertheless, many fans were outraged at Zegler’s statements, and held that grudge in the years leading up to the film’s release. Adding fuel to the fire, Peter Dinklage criticized Disney’s decision to remake the story at all given its offensive portrayal of dwarfism. And so it was little surprise when, after three years of negative press surrounding the remake, Snow White barely made $200 million and lost Disney hundreds of millions of dollars.

For what it’s worth, I found the remake to be surprisingly decent, but many disagreed. This was an interesting case in which the audience did care about the “accuracy” of the remake, unlike other older films that Disney has remade with more audience leeway, and this miscalculation by Disney cost them dearly.

But what core elements make up the Snow White story, and what differences cause it to stray too far? At face value, there are certainly plenty of plot similarities.

In both versions of the film, a beautiful young princess is hated by her stepmother, the evil queen, for being the “fairest of them all.” The queen instructs a huntsman to kill the princess, but instead the huntsman sends her into the woods, where she meets and befriends seven dwarfs. The evil queen finds out that the princess is still alive, disguises herself as an old hag, and convinces her to eat a poison apple, which puts her into a deathlike sleep until her love interest finds her and kisses her to bring her back to life.

So is that enough to move Snow White further left on the Thesian Line? Perhaps. But the story also has key differences, largely in the characterization of its heroine, that make it far less recognizable as a remake.

Just look at the “I Want” song in each iteration. 1937’s “I’m Wishing” shows Snow White simply wishing for her true love to find her, as evidenced by the short and simple lyrics (“I'm wishing / For the one I love / To find me / Today”). By contrast, “Waiting on a Wish” from 2025’s Snow White is more layered and complex, much like its protagonist. Snow White expresses the desire to become her true, brave self and live up to the legacy of her father while still breaking free of the expectations and limitations placed on her (“So will she rise or bow her head? / Will she lead or just be led? / Is she the girl she always said she'd be?”).

This song points to the larger theme of the film: that a good leader (or good person for that matter) should strive to be fearless, fair, brave, and true. Now the use of “fair” here is a clever nod to the original’s famous “fairest of them all” line, but takes on a completely different meaning. Snow White, while beautiful, isn’t the “fairest” because of her appearance, but because of her honest and just character. These are great traits for a main character. But they’re traits that were never the focus of the original film’s hero.

Snow White’s recharacterization informs many of the film’s changes, big and small. She isn’t rescued by a prince and whisked off to his kingdom; rather, her relationship with a non-prince love interest is fully developed throughout the film and his kiss isn’t the film’s culmination. The evil queen isn’t chased by the dwarfs and struck by lightning. Instead, Snow White confronts her in front of the entire kingdom, defeating her not through violence, but through those same traits of bravery and truth.

Are these differences enough to separate this entity from its original work? Or is it still recognizable as the Ship of Theseus? While it doesn’t differ to the degree of Pete’s Dragon, I do consider 2025’s Snow White vastly different from the original. The differences in characterization are simply too great, to the point where even the film’s similarities feel manufactured rather than organic.

“People Do Get Left Behind”

This year’s Lilo & Stitch remake had a much different road to release than Snow White. Originally planned as a Disney+ original, it was announced last year that the film would have a summer 2025 theatrical release instead following a smooth production and a shift in Disney’s streaming model (last year’s Moana 2 also shifted from streaming to theatrical).

The adorable blue alien has had a remarkable staying power in pop culture, with no shortage of merchandise sales, spinoff shows and sequel films in the 23 years since the original film’s release. That popularity further proved itself upon the remake’s release, breaking the box office record for Memorial Day weekend, grossing more than $1 billion worldwide within two months of release, and receiving a good (if not great) review aggregation of 71% on Rotten Tomatoes.

As expected, of the two 2025 Disney remakes, Lilo & Stitch on the surface appears to be the more faithful. The plot remains largely intact, with a troublemaking alien landing in Hawaii, being adopted by a lonely little girl, and learning the meaning of goodness and family. But the film’s ending reveals a significant thematic shift, largely driven by a reframing of character perspective.

In the 2002 animated original, the story is unmistakably Lilo’s. The film filters the world through her eyes, presenting adult conflicts (social workers, grief, economic hardship) with a childlike surrealism. Even when adults converse, we’re frequently listening to that conversation from Lilo’s perspective, overhearing conversations from another room and seeing her reaction to them. Nani, Lilo’s older sister and guardian, is a key figure, but is almost always seen from Lilo’s emotional vantage point. Stitch, as chaotic and broken as Lilo, could be considered the co-lead, and their mutual healing becomes the story’s heart.

The live action remake, however, redistributes narrative weight. Nani, previously a supporting character, is given far more screen time and POV. Certain scenes and conversations with Lilo are written and shot from Nani’s perspective, with some scenes not even featuring Lilo at all. In the climax (as a whole the largest departure from the original), it’s Nani who heroically rescues Stitch from drowning, using her abandoned swimming and surfing skills that the film had frequently alluded to.

But it’s the film’s final moments that reveal the greatest change. Nani chooses to leave Lilo in the care of neighbors while she attends college, a decision that directly contradicts the original film’s defining mantra: “Ohana means family. Family means nobody gets left behind.”

Director Dean Fleischer Camp’s justification speaks volumes: “We wanted to tell a story that’s honest about what it means to lose everything and still find a way forward. People do get left behind.”

This admittedly may feel like a nitpick to some, especially considering the rest of the film’s reverence for its animated counterpart. But it’s just such a strange recontextualization (and, frankly, misinterpretation) of what Lilo and Stitch should be. Rather than idealizing familial sacrifice, the remake leans into a nearly toxic form of individualism. Is it realistic that “people do get left behind,” as Camp put it? Sadly, yes. But why is that a choice that this film made, especially when the theme of the 2002 original was completely to the contrary?

That’s what makes this film’s placement on my Thesian Line challenging, causing me to question yet again what actually constitutes a film’s identity. The characters are still named Lilo and Stitch. The setting is still Hawaii. The central “alien-hijinks-meets-broken-family” premise remains. But the soul of the story — that family means sticking together no matter what — is fractured. The 2025 remake may resemble the original in structure, but thematically, it asks an entirely different question.

The Ship Sails On

In June 2025, Universal Pictures began their own foray into the world of live action remakes, releasing the live action How To Train Your Dragon a mere 15 years after the 2010 animated original. The film is a bizarre experience, containing nearly identical story beats, dialogue, music, and even shot selections as the animated version, far beyond that of the aforementioned remake of The Lion King.

The How To Train Your Dragon remake points to a troubling trend. With Disney and now Universal continuing these remakes, one can only imagine that this movement will grow throughout Hollywood. And whether the remakes are frustratingly identical or nigh unrecognizable in comparison to their originals, their strange existence makes my Thesian Line all the more challenging to compose.

While Disney’s strange and varied approach to live action remakes have fascinated me for years, their 2025 output really was a sort of breaking point for my system, as both Snow White and Lilo & Stitch challenge simplistic placement on the Thesian line. These films prove that even small shifts in character, theme, or emotional centering can fundamentally alter a story’s identity.

Snow White offers a modernized heroine with agency and ambition but still builds to the famous poison apple. Lilo & Stitch trades its message of unwavering familial unity for one of self-care above all, but still focuses on an alien befriending a little girl.

What these 2025 films ultimately force us to confront is a larger question: what is the purpose of these remakes? One could say it’s to preserve and reintroduce a beloved story. Perhaps it’s to reframe films for new audiences with updated values and narrative preferences. Or, most cynically, maybe these films are just nostalgic bait meant to cash in on the childhood memories of audiences.

My wife and I recently welcomed a son into the world, and I already have a running list of all the films he should see once he’s older. But my reflections on Disney live action remakes have me questioning whether Disney Studios wants to introduce young viewers to their newest, shiniest films or to their rich history of animated cinema.

When do these updated films become replacements?

How much reinterpretation can a story withstand before it stops being the story audiences loved?

Which matters more: the story we remember, or the story a new generation requires?

And if they’re not the same…is it still the same ship?

This is such a deep and thorough analysis! Thank you for this.