Start Your Engines: Unpacking the F1 Film Sound Design

A deep dive into the behind-the-scenes process that shaped the film's distinctive sound.

F1 roared into theaters this summer starring Brad Pitt as Formula One driver Sonny Hayes, who returns to racing after a 30-year absence to save his former teammate’s (Javier Bardem) team from collapse.

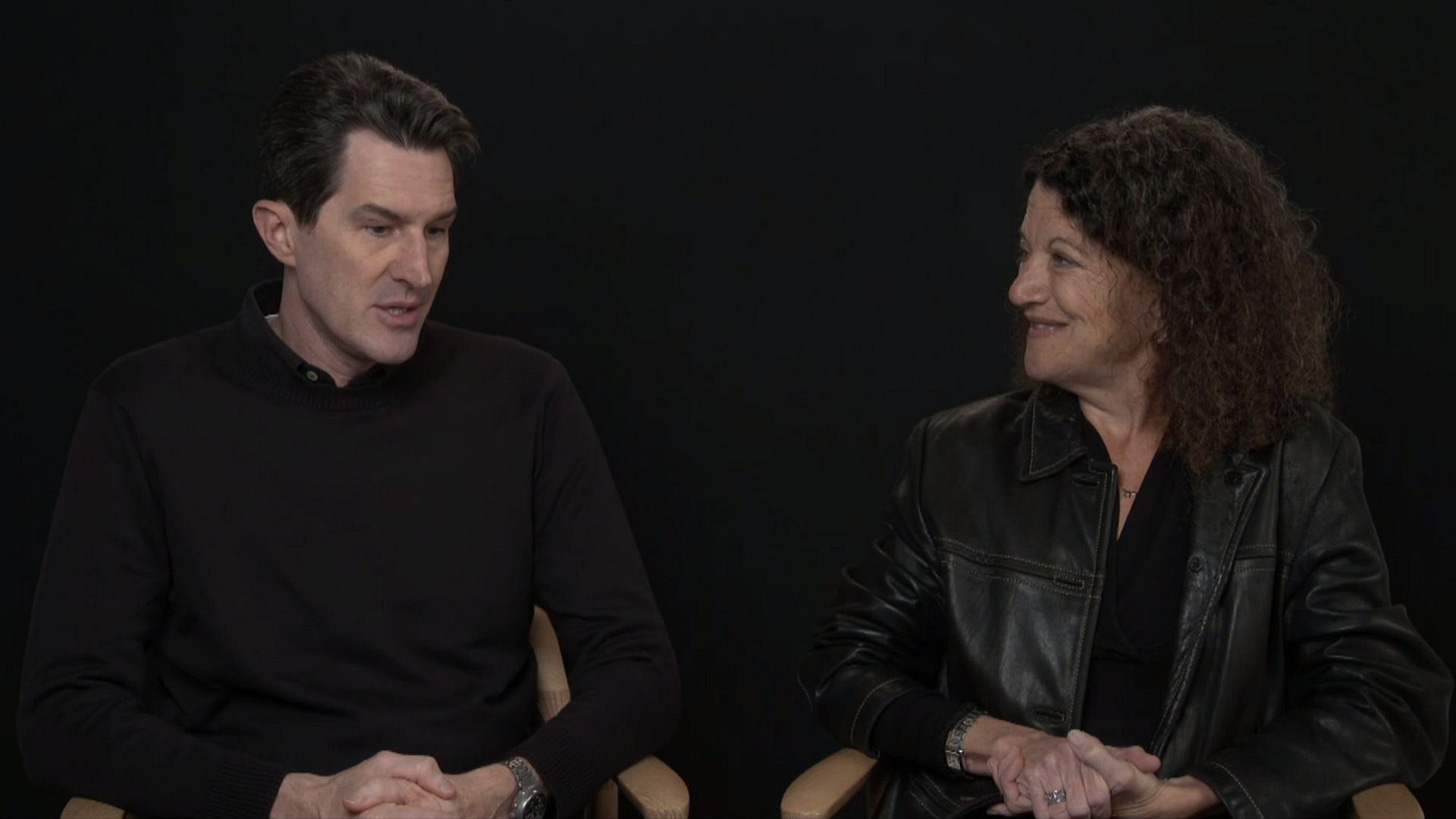

When director Joseph Kosinski began shaping the sonic identity of F1, he knew authenticity was key, shooting on location during real Formula One races and involving some of the world’s top racers in the production process.

The resulting film is a visual treat to be sure, but as a composer, I found myself drawn to F1 as an audio-immersive experience. It’s among the year’s best, with meticulous sound mixing and a heart-pounding soundtrack that reflects the thrill of Formula One.

Last month I had the pleasure of participating in press conferences with Kosinski, songwriter Ed Sheeran, and actor Javier Bardem, and asked each of them about how the film’s soundscape shaped (and was shaped by) their experience in the film. Their answers offer a revealing look at how sound became one of F1’s most essential storytelling tools.

“A Constant Soundtrack”

Kosinski’s films are known for iconic soundtracks and musician collaborations, from Tron: Legacy with Daft Punk, Oblivion with M83, and Top Gun: Maverick with its blend of score and original songs. But F1 demanded something more ambitious. “Anyone who’s been to an F1 race knows there is almost a constant soundtrack going when you’re at the race,” he noted. “It almost has a festival-like atmosphere.”

The global nature of Formula One also encouraged the director to think internationally when it came to musical selections. “I thought the songs we picked could reflect the global nature of [the sport],” said Kosinski, emphasizing how central the music’s sonic diversity was to the film’s identity.

That ambition became a creative and technical challenge: how do you balance a thunderous real-world sport with a musical score (let alone a series of original songs) without disrupting the edit or muting the emotional beats?

For Kosinski, the solution was to give each race its own sonic identity. “No two races were the same in the approach,” he explained, “whether in how we told the story, how we cut the sequence, or even the sound mix.”

Some races stay objective, letting the audience hear the crowd and the announcers as if they’re watching from the stands. Others place the viewer inside Sonny’s head, like the Las Vegas sequence where “all the other sounds disappear and you’re with him and feeling [the] score.” Those choices were part of the team’s constant effort to keep every race fresh and purposeful.

“Punch Through the Sound Mix”

Speaking of the score, Kosinski re-partnered with Top Gun: Maverick composer Hans Zimmer to develop a score that would complement the intensity of the racing sounds. “Hans and I talked a lot about what kind of score is going to be able to punch through this sound mix,” Kosinski recalled, “because these cars are intense.”

Zimmer returned to his electronic music roots to craft cues that wouldn’t get lost in the engine noise, but F1’s emotional journey required more than simple club beats. “In the dramatic scenes [the score could] go to a more orchestral and melodic place,” Kosinski said, adding, “No one writes a better melody than Hans Zimmer.”

F1 may not stand out among Zimmer’s filmography as particularly unique. He’s written for racing films before (Days of Thunder, Rush), and has frequently utilized electronic-heavy sounds (Chappie, Dark Phoenix). But if anything, F1 feels like a culmination of his career’s work, a blend of everything he’s written and performed since 1979’s Video Killed the Radio Star (yes, he was a member of The Buggles).

The titular score track, “F1,” perfectly introduces the score’s key elements, pulsing synths, propulsive drum machines, and a sweeping string melody. Meanwhile, softer tracks (No One Drives Forever) take that same melody but remove the percussive elements, creating a gentle, but emotional heart for the film.

With F1, Zimmer and Kosinski proved their powerful partnership from Top Gun: Maverick wasn’t a one hit wonder. But with Kosinski’s vision for a “global” soundtrack still to be realized, the score now had to coexist seamlessly with original songs – some still unwritten during production.

“A Really Big Rock Song”

That’s where Ed Sheeran came in.

Upon being hired to write and perform the film’s end title song, Sheeran was shown 40 minutes of the film and asked Kosinski for important phrases or concepts from F1. “It’s lovely to be brought in at that point of a movie,” Sheeran told me. “You actually feel like you’re part of building something rather than brought in as an afterthought at the end.”

In just two days he had written Drive, a “memorable piece,” as Kosinski calls it, still impressed by the speed and clarity of Sheeran’s creative response.

The song is a deviation from what fans may expect, an upbeat rock track that sounds quite unlike Sheeran’s well-established musical style. But, much like Zimmer’s return to electronica, Drive represents a musical homecoming for the English artist. “That’s the music I grew up listening to,” he fondly shared. “Those are the riffs that I learned from age 10. So, actually getting to kind of flex that muscle of picking up an electric guitar again and making something that’s really riff based, it was fun.”

From the “chugging” guitar riff to the rhythmic verses and soaring chorus, the song is a powerhouse of pure force that matches the film’s intensity. Sheeran described it as an attack on the senses, “which is essentially what F1 racing and driving is.” He was also quick to point out the valuable contributions of legendary drummer Dave Grohl and guitarist John Mayer, calling Drive “the sum of all its parts.”

As for his song’s integration with the score, it was important not to simply imitate Zimmer’s style. “I’ve known [Zimmer] for 13 years,” said Sheeran. “And we’ve always had a really good relationship. But his score is very different to the songs. This very much needed to be a really big riff-based rock song. The soundtrack and score complement each other, and there are bits that are woven in, but they are two separate entities.”

“It’s a Work of Art”

With Kosinski’s commitment to capturing the authenticity of racing, the F1 film sound design was always going to be a rigorous effort. That process actually started on set, where the actors were dealing with the very real challenge of acting and performing dialogue over the roar of real Formula One events.

For Javier Bardem, who plays team owner Rubén, that overwhelming sound was a constant component of his on-set experience. Most of Bardem’s scenes unfold inside the team garage, just feet from the race cars piloted by Pitt and co-star Damson Idris. “Damson and Brad driving themselves in those real races… crazy,” Bardem said. “They loved it. They couldn’t wait to get in the car.”

With that kind of noise surrounding him on set, I asked Bardem if it shaped his performance. “The sound that I was receiving as Rubén was ‘VROOOM,’” Bardem recalled, laughing as he mimicked the sound of the cars and the crowd.

But his immediate concern was whether any of his dialogue would survive above the noise. “I was like, ‘Okay, is there any of the dialogue that I’m going to have to do ADR? Basically all of it, right?’” But the crew exceeded his expectations. “The sound department did an amazing job, and I didn’t have to do much ADR.”

Real world Formula One champion Lewis Hamilton also became an unexpected part of the sound process during post-production. Kosinski would show him early cuts of the race sequences with a rough mix, and Hamilton would immediately spot things no one else could.

“He’d say ‘Oh, I’d be in fourth gear here, not third,’ or ‘I would shift 30 feet earlier,’ or ‘You should feel the pit wall on the right side because you’d hear the engine resonating.’ That kind of detail you wouldn’t get from anyone else,” Kosinski mused, noting that Hamilton’s involvement set the bar high for the film’s sound team.

Bardem may have questioned the sound approach during filming, but his appreciation for the finished product crystallized during his first IMAX viewing. “I sat down and I saw the movie with the sound design and I was like, ‘Jesus, the detail.’ The amount of work that they put into those moments on the racetracks are pretty amazing. It’s a work of art what they did,” Bardem says, describing the meticulous layers that brought the F1 film sound design to life.

Across all my press conferences, it became clear that the success of the F1 film sound design is the product of collaboration. Everything from Kosinski’s directorial instincts and Zimmer’s kinetic score to Sheeran’s rock experimentation and Hamilton’s technical input contributed to, as Bardem put it, “a work of art.” And like any good work of art, its power comes from the collective imprint of the many hands – and ears – that shaped it.

F1 is streaming now on Apple TV, and can be purchased on 4K, Blu-ray, DVD, or digital. So start your (TV’s) engines, crank up the volume, and enjoy the sonic immersion of Formula One racing.

Fascinating deep dive into how sound architecture shapes narrative momentum. The detail about Sheeran writing the end title in two days after being shown key phrases is wild becuz it shows how constraints can acutally accelerate creative output. I worked on a documentary where we had to redo the entire soundscape post-festival screening, and that pressure somehow produced the most cohesive audio layer of the whole project. When sonic identity gets treated as storytelling infrastructure rather than just atmosphere, everything els clicks into place.